Ulstein: Installation vessels can already operate on hydrogen today

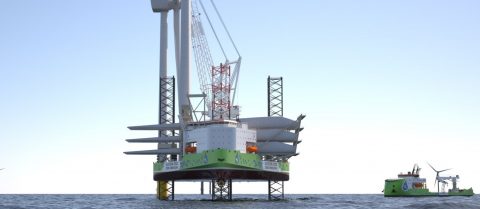

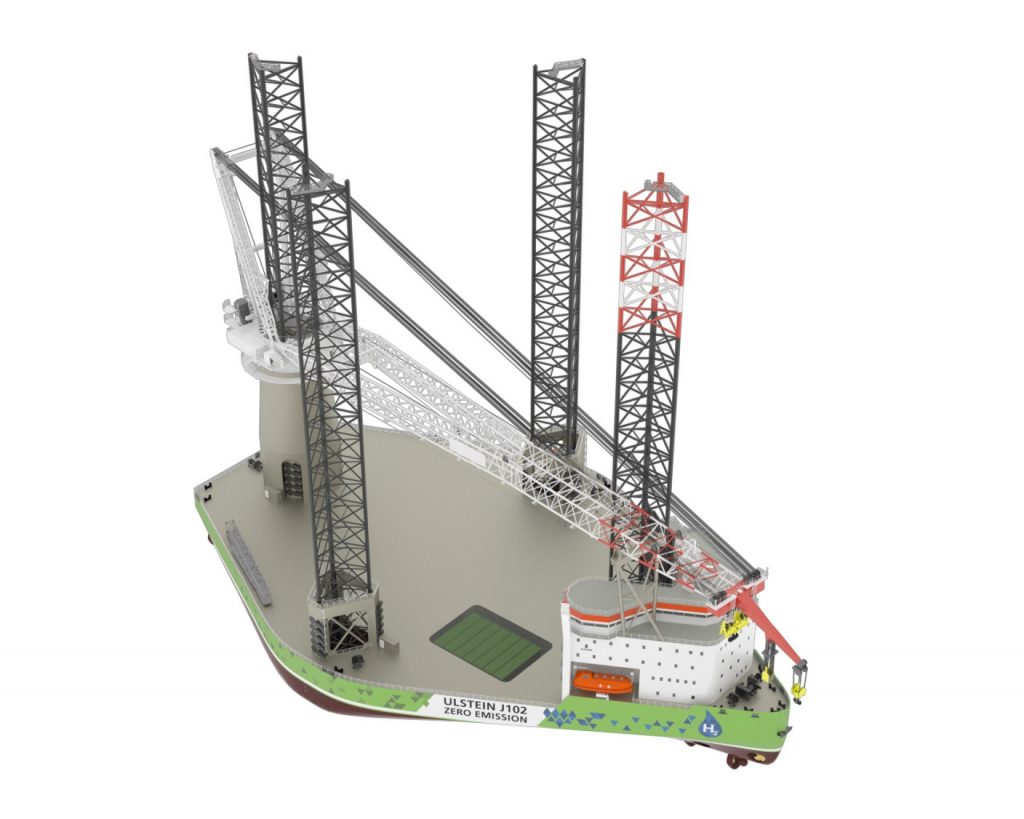

Ulstein has designed its second hydrogen hybrid installation vessel for the offshore wind industry, the Ulstein J102. It can operate in zero-emission mode 75% of the time using readily available technology. “We have designed a jack-up that can keep up with the energy transition”, says sales manager Nick Wessels.

The J102 is the second-largest unit in the X-Jack series and measures 142 metres long and 87 metres wide and has a 2,500-tonne crane. It features a kite-shaped hull allowing for large leg spacings. The main crane is installed around the stern leg on centreline. The patented layout with a simple cruciform primary structure achieves a 15% steel weight reduction compared to other jack-ups of similar capacities.

“There is space on board for 4 turbines of 17 MW or 5 of 12 MW, such as the Haliade-X. The larger version of this jack-up (J103) could also be equipped with a 5,000-tonne crane, but of course, there must be demand for it” says Wessels.

CO2 reduction of the hydrogen hybrid is said to amount to 4000 metric tonnes per year. The emission reduction per installation cycle amounts to 25%. The H2 fuel cell system consists of a PEM fuel cell. Compressed H2 is stored in 7 40ft containers and the ship is equipped with battery energy storage.

“We have carefully analysed the operational cycle of wind turbine installation vessels (WTIVs) and looked at the power demand in the various modes of operations”, says Ko Stroo, Product Manager at Ulstein. “This analysis showed that circa 75% of its time, an installation vessel is in a jacked-up position performing crane operations. Using a combination of a hydrogen fuel cell system and a relatively small battery energy storage system (BESS) is then sufficient to meet the overall power demand on board and crane peak loads.”

This means that 75% of the time, the hydrogen hybrid jack-up will be able to operate emissions-free. The technology for this is available today. The remaining 25% it operates on a diesel-electric installation. “Everyone is talking about the future and making ships hydrogen-prepared, but we have focussed on what can be achieved with the technology that is already there”, says Wessels. “That is why last year we started with an existing design of ours, a construction support ship, to see how far we could get in zero-emission mode with already existing technology.”

ARTICLE CONTINUES BELOW PICTURE

Wessels continues: “The main problem is that there is no bunkering infrastructure for hydrogen. Yet, if you look at the technology that is available: you can get hydrogen tanks containerised, fuel cells are already there in sufficiently large power ranges, you can just develop a ship that can operate fully on hydrogen, albeit for a limited time.”

The length of time a ship can operate this way is now mainly determined by the storage technology, explains Wessels. “The hydrogen is now stored in a pressurised gaseous form (500 bar). However, once you can store it as a liquid, you get ca. 3 times more energy from a similar size tank/container. Then we arrive at a ship that you can operate completely emissions-free in DP mode for 13-14 days.”

Using readily available technology, the additional cost for the jack-up is said to be limited to less than 5% of the total CAPEX.

From containerised to tanks

“We opted for a containerised solution because you can simply place it on and remove it from the ship with its own crane. The containers can be brought to the ship by truck. Those containers are already road-certified. Then such a ship can be used all over the world. You still have a diesel-electric plant on board, but you can choose to operate part of the time in zero-emission mode, for example during installation work or when you are in a port area”, Wessels states.

“As soon as the bunkering infrastructure becomes available, you can use the space where the containers are currently located for tanks. And those tanks can handle 2x 300 m3 of hydrogen and then you can just sail in DP mode on hydrogen for a month. What you then have is a vessel that can keep up with the energy transition. This will prevent the technology from catching up with you in five years time. That is what people are all afraid of now.”

Wessels does not think that hydrogen is an immediate solution for all types of ships. “I do not think that hydrogen will apply to a large ocean liner, for example. In any case, I do not see that happening in the shorter term. What we focus on is on ships that are regularly in port. You can already take the first steps towards zero-emission operations. One can wait for technology to be matured or have a vision of the future, but people sometimes forget what is already possible today.”

A longer version of this article first appeared on SWZ|Maritime, a sister publication of PCJ.