‘Was Hansa Heavy Lift too specialised?’

Was Hansa Heavy Lift too specialised? This question asks market analyst Susan Oatway of Drewry now that the bankrupt shipping line is selling off its ships in order to settle outstanding bills.

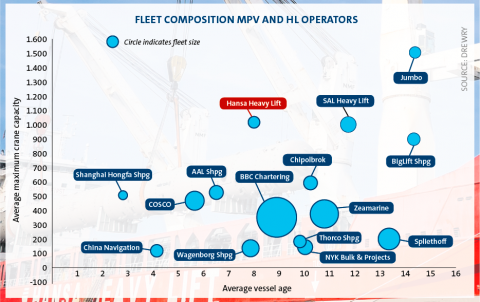

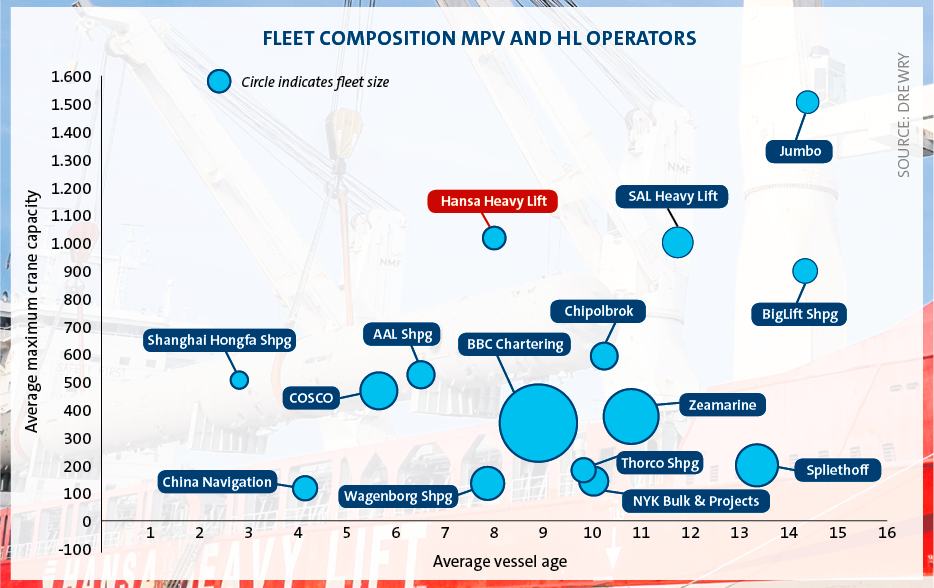

The Hamburg-based shipping line previously managed a fleet of 14 heavy lift vessels, including ten so-called ‘premium project carriers’; general cargo vessels with a crane capacity of more than 600 tonnes that are primarily aimed at large, heavy and complex loads. And since the drop in oil prices, that kind of cargo has been in very short supply.

After ten bad years, Oatway is finally optimistic again about the future of the general cargo market. 2018 saw an increase in demand of 2.8% and this year a growth of 1.5% is expected, despite a disappointing start of the year as a result of the trade war between the US and China. The problem for project carriers is that the growth mainly lies in the smaller cargo segments, which can be transported cheaper in simpler multi-purpose vessels or even in containers. That leaves little or no work for the project carriers.

As a result, Hansa suffered tremendous losses in recent years. According to figures filed with the German trade register, these mounted to net 50 million euros and 38 million euros in 2015 and 2016, respectively. The company has yet to publish more recent figures, but according to Oatway 2017 and 2018 were two ‘very difficult years’ for project carriers.

Jumbo

Like Hansa Heavy Lift, the Dutch shipping lines BigLift and Jumbo Maritime also focus on heavy project cargo. The similarities between Hansa and the latter in particular are substantial. Jumbo also has a fleet of ten large heavy lift vessels, but with hoisting capacities that go as high as 3,000 tonnes, double that of the largest Hansa ship.

Jumbo is going through difficult times as well. In 2016, the ship owner was forced to slim down in response to low oil prices. The company’s exact annual figures are not known, but shareholders Javelin Capital and FairPlay Scheepvaart B.V., who each hold 50% of the shares, booked net losses of eight and ten million euros respectively in 2017.

One important difference, however, is that Jumbo expanded its activities in 2017 through a comprehensive and exclusive collaboration with BBC Chartering, the largest general cargo shipping line in the world. Under the name Global Project Alliance, the companies joined forces commercially and operationally, providing Jumbo access to a large fleet of more basic and smaller general cargo vessels. Hansa was not involved in any such collaboration.

Consolidation

Notable is that such a combination of simpler multi-purpose vessels and specialised heavy lift ships has been regularly sought in the mergers and acquisitions of recent years as well. In 2016, Danish company Thorco Shipping and United Heavy Lift from Germany joined forces and established the joint venture Thorco Projects; as part of this, they merged their fleets of freight and crane vessels to focus specifically on the project market.

Another example is Zeaborn’s take-over of bankrupt ship owner Rickmers-Linie, which expanded Zeaborn’s fleet of multipurpose vessels with nine premium project carriers with a crane capacity of 640 tonnes. The range in crane capacity increased even further to 1,400 tonnes when Zeaborn joined forces with Intermarine and formed Zeamarine, although that move had much to do with scale as well.

Specialisation

Newbuild orders show there is a clear shift among multipurpose operators towards geared vessels with greater crane capacity. Due to fierce competition from the container and bulk sector, general cargo shipping lines have increasingly started to specialise in order to distinguish themselves, Oatway explains.

Compared to 2016, when container shipping experienced a substantial downturn, the intensity of the competition from that market has decreased, but a large percentage of general cargo is still transported by competing sectors. ‘Once it’s in a container, it won’t come out again’, Oatway said in an earlier interview with PCJ.

The current growth figures also reflect this development. While global breakbulk demand is expected to grow with 1.5%, the growth for the multipurpose and heavy lift market is only estimated at a half percent, Drewry states.

A clear sign of further specialization is Jumbo’s most recent fleet expansion; it has commissioned the construction of a heavy lift crane ship with helideck, x-bow and dynamic positioning (DP2), clearly hinting that Jumbo aims to expand its activities in the offshore (wind) industry.

Jumbo’s move is hardly surprising. According to Oatway, renewable energy currently is one of the few growth markets for heavy lift shipping lines. But the lesson for ship owners that can be drawn from the bankruptcy of Hansa Heavy Lift is that it’s also possible to be too specialised.

You just read one of our premium articles free of charge

Register now to keep reading premium articles.

Are you already a subscriber?