PCJ Live: The industry urgently needs more MPP vessels

The global fleet of multi-purpose (MPP) vessels is shrinking, as demand for offshore work is increasing rapidly. Serious bottlenecks are to be expected in Europe by 2030.

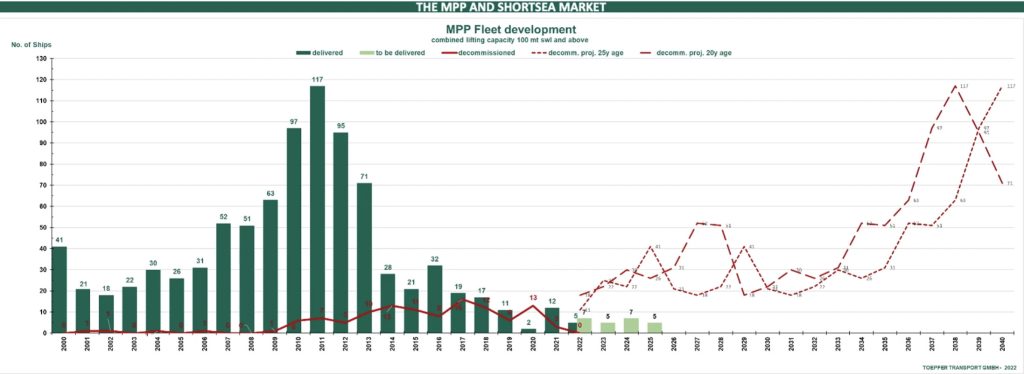

“The MPP fleet is getting older and older,” warns Yorck Niclas Prehm, head of research at Toepfer Transport, during the Project Cargo Live Webinar that took place on 15 December 2022. Indeed, the average age of an MPP vessel will be 17 years, from January 2023 on. Additionally, the order book for MPPs only represents 3% of the current fleet, which means that only approximately 30 MPP vessels are in the process of being built.

This signifies that over the next five to ten years, around a quarter of the global fleet will be leaving the market, with the production of new-build vessels being insufficient to compensate for this loss. Furthermore, “the second-hand market does not offer much relief as it also remains quite tight,” explained Prehm during Project Cargo Summit 2022. In addition, these are not the vessels that provide the needed efficiency. “Also, most ships under construction these days are already under long-term contracts so we won’t see them on the open market,” adds Prehm.

Because of this, “The global MPP fleet will get slower as demand is going up,” explains Prehm. “This is something we’ve been saying for years now. We’re going to face a rapid change in supply and demand balance.” This will be an issue in reaching renewable energy targets, which are highest in the European Union. Lastly, “some premium shippers require that ships be below 15 years of age due to high cargo insurance premiums.”

Sustainability standards

The projected scrapping of ships will also be increasing more rapidly, particularly from 2026 on, accelerated by environmental regulations. Shifting standards are also a factor in the shrinking of the MPP fleet. Indeed, “There was a huge amount of MPP deliveries in the early 2000s, up until 2011,” states Prehm. “There were lower standards for building back then, with lower environmental regulations. Ships were built with high levels of fuel consumption.” Additionally, the economic lifespan of ships built during that period is up to 25 years.

Though there are options available to extend the lifespan of ageing vessels, including slow steaming or installing new scrubbers, “When a ship reaches a certain age it does not make sense to invest massively in it,” states Prehm. Indeed, the investment return period depends on the market. For example, that period is of seven to ten years for scrubbers, according to Prehm. “It also depends on the fuel prices which are very volatile, especially now with too many geopolitical factors,” he adds.

A key issue facing the shipbuilding industry is that of ‘fuel hesitancy.’ A wide variety of alternatives to hydrocarbon fuels are currently in the running to become part of the fuel mix that will power the shipping industry in future. As a result, vessel owners are not certain as to which type of fuel will be readily available in ports globally. This has led to a hesitancy to order new vessels until the bunkering infrastructure is more developed. Indeed, “It is still risky to be an early adopter of green fuel technology,” says Prehm.

Rate development

According to Prehm: “What we’ve seen in the rate development in the past 18 months, is that rates went up rapidly due to heavily increasing demand, which could be foreseen for MPP ships, and at the same time as well as overspill and well-paid cargo from the container operators.” From an owner and carrier perspective, this was a positive development, as rates went up “from a pretty unhealthy level to a healthy level, and then an overheated level,” he adds.

“We see a correction movement over the past month. Since summer the rates have gone down about 6% per month. We will see the bottom of this downward trend pretty soon, we believe that that will happen at the end of Q1 of 2023,” posits Prehm. “With regards to our index, what we consider a healthy level is between 15 and 18 thousand dollars a day, which would sustain investment into new buildings.”

Of course, you need the perspective of long-term earnings to make such investments. There is not much investment yet, for various reasons. Rates are going down while interest rates are going up. New-building prices are relatively stable but there is a recession coming up, and inflation continues to worsen. There are also too many uncertainties relating to fuels,” explains Prehm.

Cluster risk

“At the moment, except for four ships being built by a Dutch shipyard in Germany, the whole MPP order book comes from China. With all the political uncertainties in this regard, we have some kind of a cluster risk,” highlights Prehm. In stark contrast to several Asian countries, only 5% of MPP vessels ordered by European actors are manufactured locally. Comparatively, China only orders 1% abroad, South Korea 9%, and Japan 30%, according to the German Shipbuilding and Ocean Industries Association (VSM).

Europe needs to be able to provide at least a basic supply of fleet for local sources to protect its economic interest. We need to look at whether we want to manufacture the ships where they are the cheapest or look at creating a minimum supply from local sources, to be safe and avoid cluster risks,” explains Prehm. For this, “A political and economic framework has to be established to re-establish, modernise and strengthen shipbuilding and supply of equipment from inside the EU.”

This is particularly important to facilitating the energy transition which will require all kinds of vessels, from MPPs to installation vessels, tugs, and barges. “The huge energy transition targets in Europe, especially the offshore wind targets, will be the peak driver for cargo demand in the MPP segment in the coming years,” says Prehm. “Time is running out. To have the fleet we need to reach wind energy targets, we must start building it now.”

You just read one of our premium articles free of charge

Register now to keep reading premium articles.